Case study:

Arthurian Cinema

Introduction

The second most popular plot referred to by filmmakers in the database is the Arthurian legends. What they have in common with the story of the Robin Hood character is the lack of a solid primary source. John Aberth echoes this, noting that, like Robin Hood, King Arthur is “the one historical figure about whom we know the least in terms of cold, hard facts”1. The first “biography” of Arthur, which served as the basis for the legendary narrative, was incorporated into “Historia Regum Britanniae” (c. 1135-1138) written by the Breton bishop Geoffrey of Monmouth. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Arthurian legends, including those of Sir Lancelot, became common in France2. The most studied source among scholars for the legend of King Arthur is the already mentioned 1470 novel “Le Morte D’Arthur”3. It is a cycle of adventures, a kind of anthology of French and English legends, centered on the key figure of Lancelot. According to Leitch4 the influence of this literary source material amongst general readers is rather negligible. Aberth, on the contrary, makes a strong case that this work, published in the midst of a political crisis, both tapped into the nostalgic mood of Englishmen, and gained popularity on both sides of the Channel. It was the legends as retold by Thomas Malory that formed the basis for most interpretations of the figure of Arthur and his entourage5.

Despite, or perhaps because of, a lack of historically accurate evidence, this character is the leader in the total number of film incarnations among other medieval figures. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table have become such a pervasive trope in pop culture and movies that it is neither meaningless nor accurate to attribute their origins to one particular literary source (unless the exact source is explicitly specified). This state of affairs, according to Haydock, has resulted in an attitude that “Arthur is capable of embodying almost any desire – romantic, rationalist, or racist; nationalistic, nostalgic, or New Age; fundamentalist, fascist, or futuristic; postcolonial, post ideological, or even post-Twin Towers”6. Legends have become so ephemeral, and meanings so blurred and malleable, that it is easy to tweak the Arthurian narrative to fit any political and cultural agenda. Yet bear in mind that King Arthur was a real-life person who lived in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. Legends about him, however, beginning in the high Middle Ages, tended to overshadow the actual biography.

How all these twists and turns of the biographies of the real and fictional King Arthur are reflected on the title cards; how and with what techniques they help to construct or debunk myths, is discussed in this chapter.

Data analyzed

Arthurian cinema is often the subject of study7. Researchers are attracted both by the portrayal of the legendary king and his cronies and by the use of the film as a propaganda tool to promote certain platforms and narratives8. The most inventive film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) which was not included in the selection due to chronological constraints has not been overlooked by academia. The database contains eight examples of Arthurian films.

- The Adventures of Sir Galahad, dir. Spencer Gordon Bennet (1949)

- A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, dir. Tay Garnett (1949)

- Knights of the Round Table, dir. Richard Thorpe (1953)

- Prince Valiant, dir. Henry Hathaway (1954)

- The Black Knight, dir. Tay Garnett (1954)

- Siege of the Saxons, dir. Nathan H. Juran (1963)

- Sword of Lancelot, dir. Cornel Wilde (1963)

- The Sword in the Stone, dir. Wolfgang Reitherman (1963)

Six of them were produced in the United States (including two in co-production with the UK), the rest in the United Kingdom solely. The major Hollywood studios of the time – MGM, 20th Century Fox, Columbia Pictures, Walt Disney Productions, and Paramount Pictures – were responsible for the production. The legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table seemed ideally suited for large-scale screen adaptations. Could the reason for such fascination lie in the desire of American filmmakers to construct for themselves the very European medieval past they did not have, their own national myths? And legendary plots about chivalry, valor, noble quests, the storylines of which can be unfolded in clichéd medieval castles, look like a perfect set-up. Another interesting feature is the chronology of the films: the first of them were released after World War II, the next one (recognized by all researchers as the worst on the historical part, and the most propagandistic) was released at the height of the Second Red Scare, and the last three – during the presidency of John F. Kennedy.

Films on this subject represent a curious phenomenon that can be categorized as a special case of medievalism9. As discussed above, King Arthur lived in the early Middle Ages, and biographical information and legends about him began to appear actively in the 11th and 12th centuries. All the films depict the High Medieval Period, which confirms their reference to the works of Thomas Malory and T. H. White, which are both characterized by the same anachronistic deviations10. Is there a similar problem in the title cards of these films?

Analysis

While there is a certain degree of creative freedom that comes from the chronological framework of the real Arthur’s life and myths about him, this advantage is not exploited in the film title cards. Moreover, the opening sequences of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1949), Knights of the Round Table (1953), Prince Valiant (1954), and Siege of the Saxons (1963) are examples of the previously encountered phenomenon of standardization and templating of studio films. By adopting the most straightforward techniques of vernacular Hollywood language, the creators managed to make completely inexpressive credits. They incorporated the most generic and inexpressive templates. Summarizing, frames with typical elements of the Middle Ages (as it is imagined by the creators and as spectators are mostly accustomed to associate with this period) change on screen. A safe scenario includes swords, furs, cups, coats of arms and shields in the interiors of the castle.

Regarding the letterforms of the title cards, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1949) and Knights of the Round Table (1953) present the most modern visuals. The lettering in the title cards of the other films refers to Gothic script gravitating towards formal grades of the 13th–14th century11.

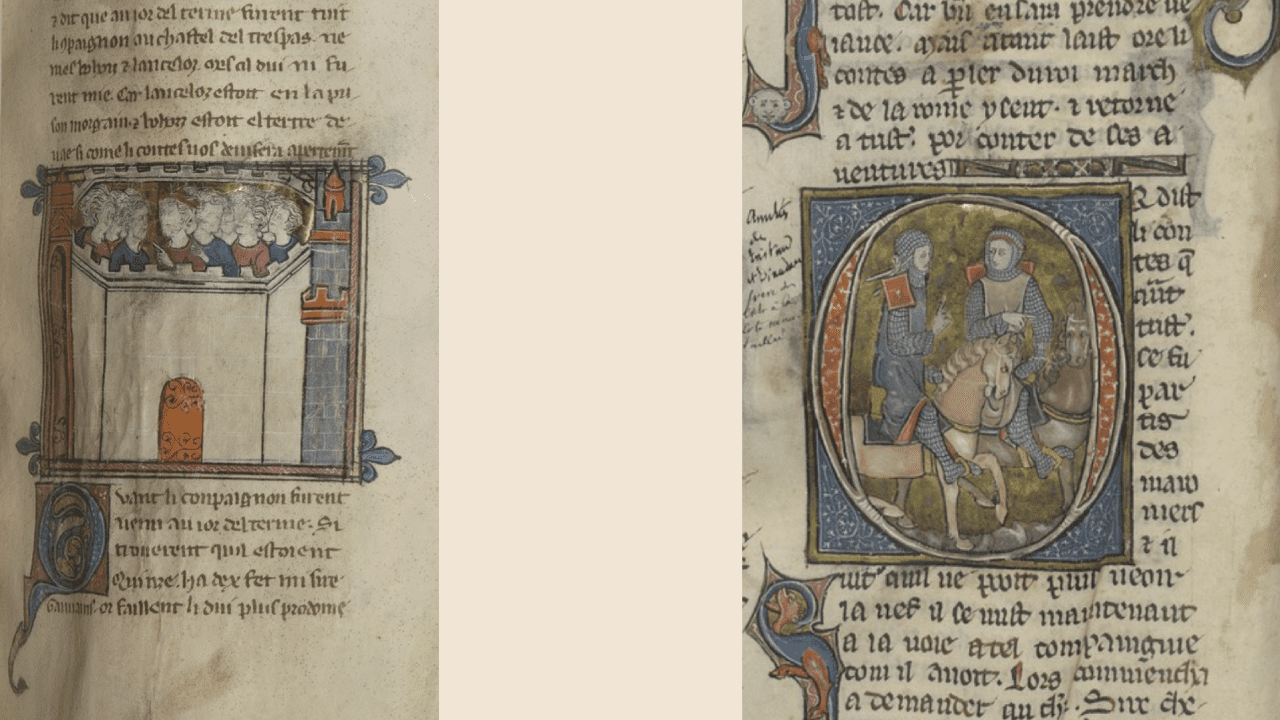

Le Roman de Tristan.. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 776, fol. 10v (on the right).

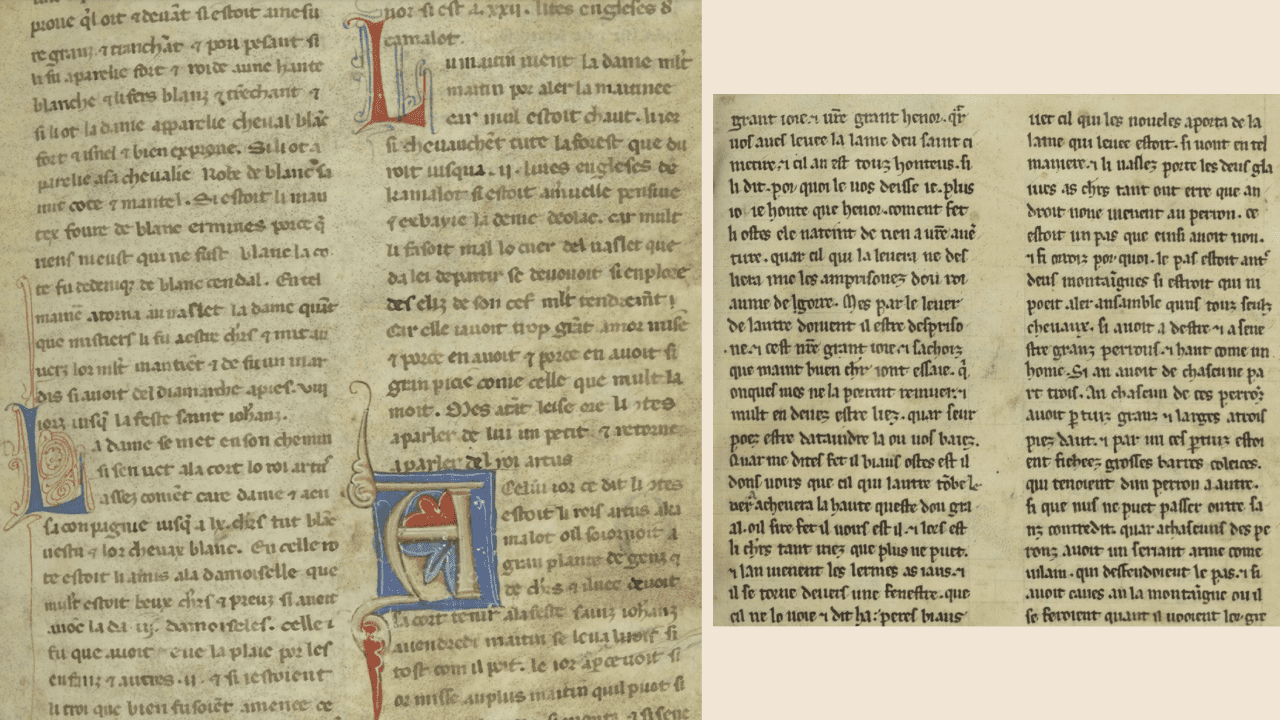

Plain page in Gothic script (fragment): Lancelot du Lac [de GAUTIER MAP]. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 752, fol. 221r (on the right).

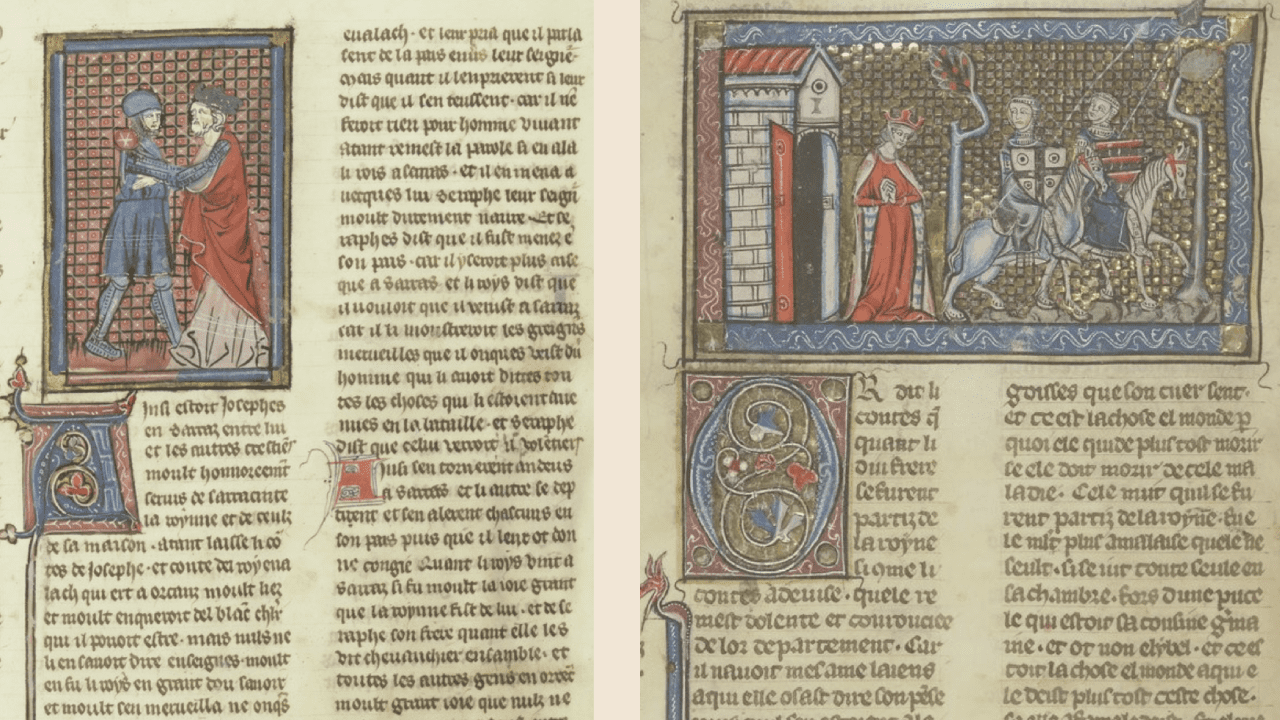

Lancelot du Lac, deuxième partie, de “mestre GAUTIER MAP”. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 333, fol. 21v.

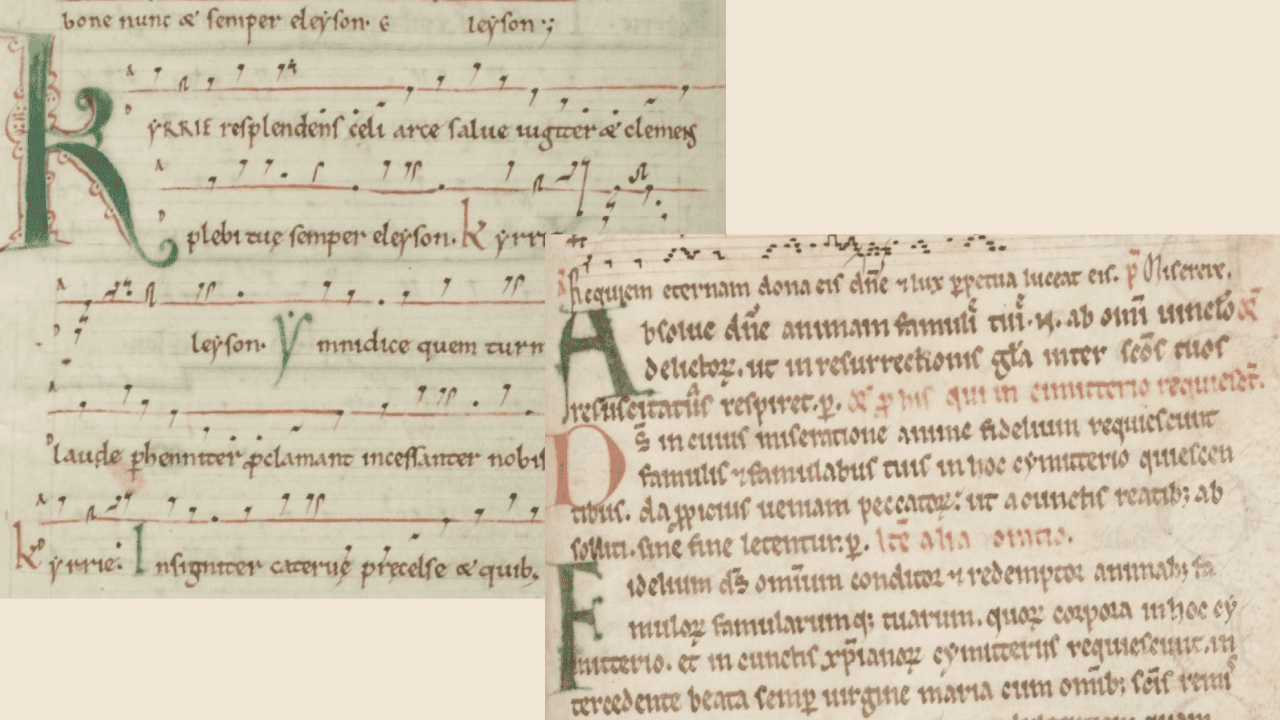

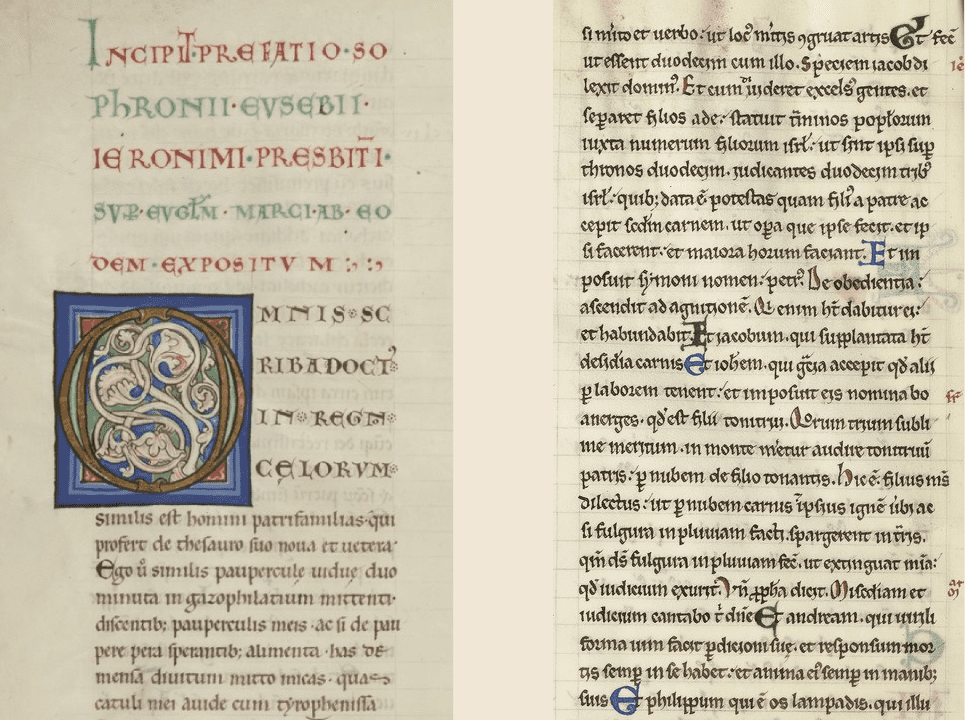

It is characterized by sharp, vertical, repeating strokes, all letters have little angular feet, while ascenders and descenders tend to be short to fit into lines. Examples of such script, for instance, are found in manuscripts including stories about Lancelot written in the 13th–14th centuries. Most of such manuscripts I have encountered are richly decorated with ornamental initials as well as skillful miniatures, and represent a common example of medieval book art.

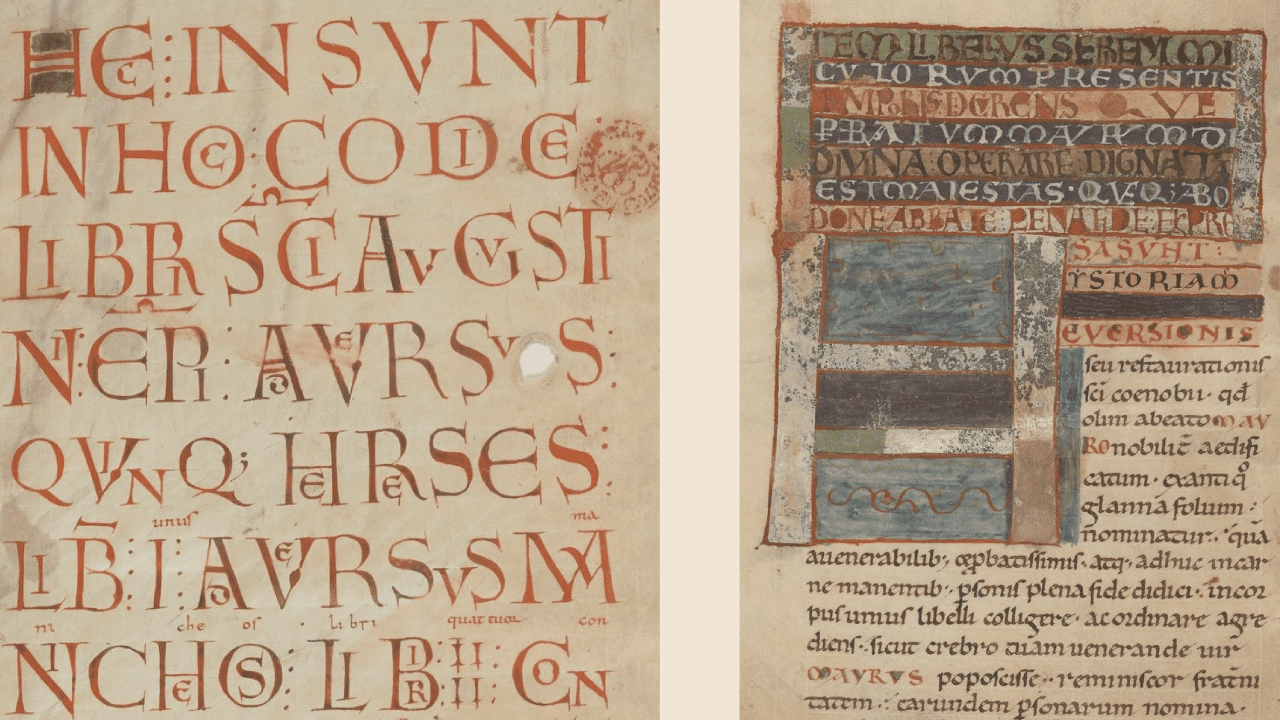

Two examples deserve attention. Sword of Lancelot’s (1963) title card is designed with an eye to majuscule letterforms12, with the exception of the modern letter “W”. The animated movie The Sword in the Stone (1963) is the only example of the use of references to magic and sorcery found in literary sources, namely King Arthur’s sword. This artistic decision echoes the plot of the movie and sets the audience’s focus on the fantasy side of the story. The use of shades of green also contributes to this effect. In manuscripts, this color, like yellow, was often used to mark the beginning of sentences and to highlight majuscules, as well as for writing titles13.

Vita sancti Mauri ; Vita metrica sancti Mauri ; Vita sancti Placidi ; Vita sancti Hilarii – Vita sancti Nicolai. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 5344, fol. 30v (on the right).

and Bréviaire de Corbie. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 13221, fol. 98r (on the right).

and an example with initials (on the right). Commentaire sur S. Marc. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 12020, fol. 14v.

Classification

The opening credits typology is predominated by a template opening sequence variant with a painted background on which stereotype Medieval attributes are placed. However, three motion pictures precede the intro. In Adventures of Sir Galahad (1949), a TV show of 15 short episodes, title cards appear against a background of short excerpts from different scenes. Hence, the title cards tie together a throughline plot. Although researchers unanimously call The Black Knight (1954) a bad movie, the opening sequence, unfolding against the background of a cavalry march, looks organic14. The serene landscape with the group of knights creates an immersion into the world of the movie before it even begins. The arrangement of the credits is also an interesting decision. This sequence appears only after the opening scene with a troubadour singing a ballad about a fearless knight. Sword of Lancelot (1963) opens with several black-and-white and sepia-toned freeze frames depicting the main plot lines. The choice of such a presentation for a Technicolor film engages with the perception in an intriguing way – it feels like watching a documentary.

The creators of the credits adapted the written tradition of letterforms from the times of circulation of recorded legends, rather than using scripts common in the 6th century as a reference point. Thus, the credits, like the films that follow them, draw on the archetype of the Middle Ages without attempting a slightly deeper immersion in historical context. The commercialization of filmmaking along with mass production (i.e., three films on the same theme were released in 1963 alone) did not encourage the expansion of the artistic apparatus and the incorporation of more specific features to the opening sequences. Notably, almost no magical features appear in the credits (except for the animated example), although such a plot is present in legends. All in all, just as American cinema appropriated the Arthurian myths, with the same insistence it has enshrined a certain image of the Middle Ages in the opening credits.

Script Examples

-

Bréviaire de Corbie. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 13221: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8427451g/

-

Commentaire sur S. Marc. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 12020: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52517112r/

-

Graduel de Saint-Évroul. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 10508: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8422969b/

-

Lancelot du Lac, deuxième partie, de “mestre GAUTIER MAP”. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 333: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10537237/

-

Lancelot du Lac [par GAUTIER MAP]. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 752: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52511544b/

-

Le Roman de Lancelot du Lac [de GAUTIER MAP], première partie. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 773: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b104636824/

-

Le Roman de Tristan. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 776: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000110d/

-

Quoduultdeus, Adversus quinque haereses ― Augustinus Hipponensis, De Genesi contra Manichaeos ; De fide et symbolo ; De fide contra Manicheos ; Collatio cum Maximino ; Contra Maximinum ― Augustinus Hipponensis (ps.), Collatio cum Pascentio. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 12219: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10551092j/

-

Roman de Lancelot du Lac, Quête du S. Graal et Mort d’Artus. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 12573: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52505724b/

-

S. Hieronymus. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 1850: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b85301860/

-

Vita sancti Mauri ; Vita metrica sancti Mauri ; Vita sancti Placidi ; Vita sancti Hilarii – Vita sancti Nicolai. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 5344: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542002v

-

Ystoire du Saint-Greal, qui est le fondement de la Table reonde, que on dit de Lancelot du Lac, et du roy Artus et des chevaliers de la Table reonde. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 9123: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10029508v/

***

-

John Aberth, A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film (New York, NY: Routledge, 2003), p. 13.↩︎

-

An overview of a rich and intricate literary tradition is available in: Susan Lynn Aronstein, Hollywood Knights: Arthurian Cinema and the Politics of Nostalgia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 29–54.↩︎

-

John Aberth, A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film (New York, NY: Routledge, 2003), p. 14.↩︎

-

Thomas Leitch. “Adaptations without sources: the Adventures of Robin Hood”, Literature-Film Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2008), p. 27.↩︎

-

John Aberth, A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film (New York, NY: Routledge, 2003), p. 21.↩︎

-

Nickolas Haydock, Movie Medievalism: The Imaginary Middle Ages (Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2008), p. 165.↩︎

-

There are corresponding chapters and reflections in every book and academic article dealing with cinematic medievalism and depicting the Middle Ages on film.↩︎

-

The most striking example is The Black Knight’s (1954) blatant anti-Communist and pro-American agenda. Also the most inventive film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) which was not included in the selection due to chronological constraints has not been overlooked by academia. A thorough examination of the use of humor and satire, and of deliberate historical inaccuracy, exemplified by this film is found in many studies examining filmic incarnations of chivalry and Arthurian legends. See, for example: Andrew B. R. Elliott, Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the Medieval World (Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2011); Laurie Finke and Martin B. Shichtman, Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010); Susan Lynn Aronstein, Hollywood Knights: Arthurian Cinema and the Politics of Nostalgia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); and many more.↩︎

-

“Arthurianism, lacking a secure historical location, is a special category of medievalism. The legend has always been adapted to contemporary concerns: anachronism is its very essence. <...> Arthurian texts regularly gesture towards history, but the era is not located in history: it is – and always has been – a multi-temporal, or extra-temporal, zone of fantasy”. Anke Bernau and Bettina Bildhauer, eds., Medieval Film (Manchester ; New York : New York: Manchester University Press ; Distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp. 30–31.↩︎

-

Ibid.↩︎

-

See examples with miniatures from 13th century: Roman de Lancelot du Lac, Quête du S. Graal et Mort d’Artus. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 12573: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52505724b/, fol. 96r; Le Roman de Tristan. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 776: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000110d/, fol. 37r; or example with decorated initials: Le Roman de Lancelot du Lac [de GAUTIER MAP], première partie. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 773: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b104636824, fol. 93; or plain text as in: Fragment de Lancelot du Lac [par GAUTIER MAP]. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 752: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52511544b, fol. 221r. Manuscript pages with miniatures from the 14th century: Ystoire du Saint-Greal, qui est le fondement de la Table reonde, que on dit de Lancelot du Lac, et du roy Artus et des chevaliers de la Table reonde. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 9123: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10029508v, fol. 32r; Lancelot du Lac, deuxième partie, de “mestre GAUTIER MAP”. “BnF Catalogue général”, Français 333: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10537237h, fol. 21v.↩︎

-

I.e., examples from the 11th century: Quoduultdeus, Adversus quinque haereses ― Augustinus Hipponensis, De Genesi contra Manichaeos ; De fide et symbolo ; De fide contra Manicheos ; Collatio cum Maximino ; Contra Maximinum ― Augustinus Hipponensis (ps.), Collatio cum Pascentio. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 12219: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10551092j/, fol. Bv; Vita sancti Mauri ; Vita metrica sancti Mauri ; Vita sancti Placidi ; Vita sancti Hilarii – Vita sancti Nicolai. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 5344: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10542002v/, fol. 30v.↩︎

-

For instance, heading in green ink: S. Hieronymus. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 1850: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b85301860/, fol. 3v; green majuscules: Graduel de Saint-Évroul. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 10508: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8422969b/, fol. 14v; Bréviaire de Corbie. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 13221: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8427451g/, fol. 98r; and an example with initials: Commentaire sur S. Marc. “BnF Catalogue général”, Latin 12020: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52517112r/, fol. 14v.↩︎

-

In the chapter on Robin Hood films, I elaborate on the idea of choosing yellow as the primary color.↩︎